Christian Migration and the Future of Global Church Planting

A 2025 Diaspora National Conference article written by Dr. Harvey Kwiyani

This article is part of an upcoming booklet to be released at the 2025 Diaspora National Conference, featuring reflections and insights from the conference's key speakers and leaders. Together, these contributions offer a glimpse into the values, vision, and voices shaping the Quiet Revival that’s happening in cities and churches across the West.

Migration is an intrinsic part of life. It is not unique to humans—birds migrate, fish migrate, and countless other animals move in search of sustenance, safety, or better conditions. Humans, likewise, have always been on the move, carrying far more than material possessions: memories, identities, worldviews, cultures, and religious traditions. The current discourse on Christian migration, at its core, is about the movement of people who happen to be Christian. This should be understood as part of the broader, recurring pattern of global history in which people of all faiths and traditions move from one part of the world to another.

In the 20th and 21st centuries, political conditions have often been favourable to Christian mobility. According to Pew Research, Christians accounted for as much as 47 per cent of all international migrants in 2024—a striking figure underscoring the role of migration in shaping the life of the Church around the world. This reflects not only Christianity’s global reach but also the various economic, political, and social factors driving Christian communities to seek new opportunities and safety abroad.

Yet this is not new. From its inception, Christianity has been a faith on the move—born in the cultural crossroads of the ancient Near East, carried along trade routes, pilgrim paths, and through displacements of exile. The gospel spread as believers travelled, whether by choice or compulsion, establishing new communities wherever they went. The early church’s expansion across the Roman Empire, missionary journeys to Ireland and Britain, the evangelization of the Americas, and Protestant missions to Asia and Africa all demonstrate this enduring pattern of faith spreading through human movement.

This historic pattern continues today, most visibly in the global church-planting work of migrant Christians. Migration does not merely relocate believers; it often transforms them into missionaries. My friend, Jehu Hanciles, rightly argues that every migrant Christian is a potential missionary. In his book Beyond Christendom, Hanciles observes that having the Christian faith most likely leads to travel. As followers of Christ, we follow the Spirit who, like the wind, blows and moves in all directions—often carrying us to places we never planned to go but where the gospel is needed.

The transformation from migrant to missionary happens naturally as believers find themselves in new contexts where their faith becomes both a source of personal strength and a bridge to new communities. Whether driven by economic opportunity, political persecution, or education, many discover their displacement to be a divine appointment—an opportunity to plant seeds of faith in previously unreached soil.

As followers of Christ, we follow the Spirit who, like the wind, blows and moves in all directions—often carrying us to places we never planned to go but where the gospel is needed.

Across Europe, North America, Asia, and Africa, migrant Christians are planting churches—sometimes to serve diaspora communities, often to reach broader local populations. These congregations breathe new life into areas where churches have declined, introducing vibrant worship, passionate evangelism, and a deep sense of mission. In London, Korean and Nigerian churches thrive in former Anglican buildings; in American suburbs, Chinese house churches multiply among immigrant groups; across European cities, African Pentecostal congregations inject energy into fading Christian landscapes.

The impact extends beyond numbers. These churches bring different theological emphases, worship styles, and approaches to community engagement that enrich the broader Christian landscape. They demonstrate faith expressions that are both deeply rooted in cultural traditions and remarkably adaptable to new contexts.

Historically, planting new churches has been among the most effective ways Christianity expanded and rooted itself in new cultures. Migrant-led church planting mirrors this New Testament pattern: the Apostle Paul, a travelling missionary, planted communities wherever he went, often in cosmopolitan, multi-ethnic urban centers. Similarly, today’s migrant Christians establish churches in some of the most secular and religiously diverse cities worldwide. These churches are not mere outposts preserving cultural traditions; they are living, missional communities that adapt, cross cultural boundaries, and engage social and spiritual needs.

Often, migrant church planters reach people that established churches cannot or will not—immigrants without local language skills, international students far from home, marginalized groups seeking belonging, and locals curious about fresh expressions of faith. These congregations often become centers of evangelism, discipleship, and community care, impacting neighborhoods well beyond their membership. Many provide social services, language classes, job placement help, and cultural integration support, benefiting entire communities.

Moreover, these churches serve as vital bridges between cultural communities, fostering understanding and cooperation across ethnic and linguistic lines. They embody a Christianity that is simultaneously local and global, rooted and mobile, traditional and innovative.

Seen this way, Christian migration is not only a continuation of a historical trend but one of the most significant mission forces of the 21st century. As migrant believers—each a potential missionary—plant churches worldwide, they embody a faith that is inherently mobile, adaptable, and transformative. They revive old mission fields, reach new frontiers, and reshape the future of global Christianity.

In a world defined by movement and change, migrant Christians stand at the forefront of mission today. They are not simply travelers or refugees—they are pioneers planting seeds of faith in new soil, cultivating communities that embody the future of global Christianity. Recognizing and supporting their church-planting work is not just a matter of hospitality; it is an urgent call to partner with God’s Spirit as it blows fresh winds of renewal across the Church worldwide.

Dr. Harvey Kwiyani is a Malawian missiologist and theologian who has lived, worked and studied in Europe and North America for the past 20 years. He currently serves as a member of the Diaspora Network Board of Directors. He will be assisting with a track at the 2025 Diaspora National Conference around planting next gen ministries out of first gen congregations, as well as leading a lunch round-table discussion on “Mission and Migration” and the “Quiet Revival” happening across the U.S. and U.K. You can read more of Dr. Kwiyani’s reflections on his Substack: Global Witness, Globally Reimagined.

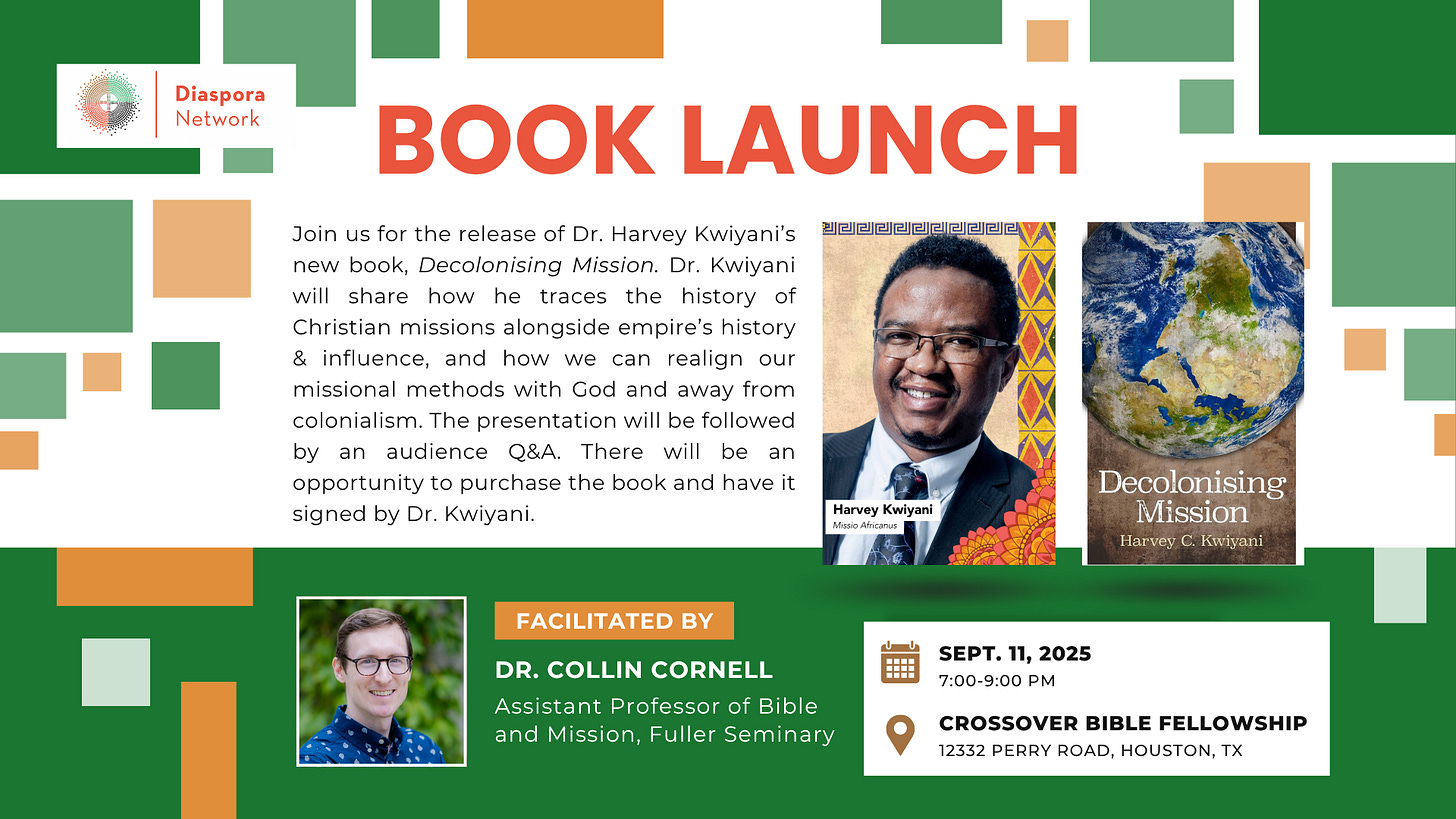

Join the Diaspora Network in celebrating the release of Dr. Harvey Kwiyani’s new book, Decolonising Mission. This book release party will take place the evening before the 2025 Diaspora National Conference in Houston, TX. Dr. Kwiyani will share about his book, followed by an audience Q&A facilitated by Dr. Collin Cornell, Assistant Professor of Bible and Mission at Fuller Seminary. Afterwards, there will be an opportunity to meet Dr. Kwiyani, purchase a copy of the book, and have it signed. Register for the book release at the link below!