Declaration on Reaching the Next Generation

The immigrant church in North America faces an Acts 6 moment.

(This declaration was originally written for and released at the 2012 Mission On Our Doorsteps Conference held in Wheaton, IL. Rev. Jonathan Kindberg, Dr. Sam George and other key leaders of the Diaspora Network were on the planning team for that conference. It is more relevant today than ever as we seek to connect and strengthen the immigrant church and empower and release the next generation of church leaders.)

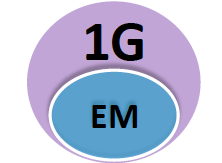

The immigrant church in North America faces an Acts 6 moment. This chapter opens with a conflict between the Hebraic Jewish leaders and the Hellenistic Jewish members over the care of their widows. The first generation of Jesus' disciples were Hebraic Jews who led the church upon Jesus’ ascension. However, the Hellenistic widows were overlooked by the Hebraic leadership in the distribution of food. The Hebraic leadership remedies this neglect by the courageously appointing seven deacons with Hellenistic background. The courage of the Hebraic leadership combined with the spiritual maturity of the Hellenistic members leads to an expansion of the gospel both in Jerusalem (Acts 6:7) as well as in Judea and Samaria by the newly appointed Hellenistic leaders (Acts 8:1).

Similarly in North America today, stories of conflict between the first and second generation abound. The first generation of immigrants can inadvertently overlook or misinterpret the needs of the second generation. These struggles are increasingly multiplying in immigrant groups across ethnic boundaries. Since the floodgates of immigration opened up in 1965, the first wave of immigrants to America from around the world have planted churches and are greying. The time is ripe for the baton and spiritual legacy of the first generation to be passed down to the next generation. However, many immigrant churches are struggling to surmount barriers of culture and language to reach the next generation, leading to what many have called a “Silent Exodus.” This issue affects not only the immigrant church but the entire country; the Pew Research Center estimates that virtually all (93%) of the growth of the nation’s working-age population between now and 2050 will be accounted for by immigrants and their U.S.-born children, and they would rise to a record 37% of the entire U.S. population.1

How will the church respond? Our first impulse is often pragmatic, fixing a problem without understanding the underlying causes. Often, we look for one successful model for all subsequent groups to follow. However, many different models of ministry have risen to reach the next generation in different ways. We want to articulate operational and biblical principles to undergird the process of reaching the next generation in the immigrant church. This is our 6:7 moment, an opportunity for the baton of leadership to be passed so that “the word of God [might continue] to increase, and the number of disciples [might multiply] greatly” (Acts 6:7).

Operational and Biblical Principles for Reaching the Next Generation:

1. We believe that the first generation has a God-given responsibility and opportunity to release and bless the next generation (Gen. 1:28; 49:1–27), both in the home (Eph. 6:4) and the church (Acts 6:3; 2 Tim. 2:1–2).

The church is always one generation away from extinction. Without the blessing from the first generation, the next generation will limp in fulfilling their own God-given calling. However, the first generation must fight the temptation to hold on to the reins of leadership but courageously give the opportunity at the right time for the next generation to lead, make mistakes, flourish and grow.

We believe that the next generation has a God-given responsibility and opportunity to honor the first generation, covering over and not unnecessarily exposing their sin (Gen. 10:18–27), affirming their authority while cultivating their own spiritual maturity (Acts 6:1–6; Heb. 13:17).

The second generation can easily blame their own spiritual immaturity on the failures of the first generation. However, just as the Hellenistic Jews (second generation) had leaders “ of good repute, full of the Spirit and wisdom” (Acts 6:3), so the second generation must cultivate spiritual maturity and earn the respect of the first generation.

We believe that generational transition is a process that takes time, and each church must honestly recognize the stage that they are at in this process and faithfully work to reach people in that stage. If we are faithful with little, then we will be entrusted with more (Luke 16:10).

Failure to recognize the process of generational transition can kill the momentum of a church If we say the right things at the wrong time, then we can do great damage to the church. If a church is wondering whether they should have a children’s ministry in English and a leader asserts the need for immediate financial independence of an English-speaking ministry, then unnecessary opposition and defensiveness can emerge. Instead, we must faithfully cultivate our churches at each stage of their development process. This means that we must honestly recognize our stage of development and work to reach people with the gospel in that stage. Just as churches work on the process of leadership transition at the retirement of their senior leadership, so churches must work on the process of generational transition with the changing of generations. This challenge is not limited to the immigrant church, but the differences in language and culture between the first and second generations exasperate the challenges of generational transition that are present in every church.

We believe that the Church needs a multiplicity of church models to reach the next generation (1 Cor. 9:19–23).

We are always tempted to see one successful model and imagine that it is the only right model. However, the diversity in degrees of assimilation and ethnic identity suggest the need for a diversity of models of churches to reach different types of people. For example, those with high assimilation to the dominant culture and low ethnic identity will likely gravitate toward assimilation into a largely Anglo-church. Those with high ethnic identity and low assimilation will likely feel most comfortable in an immigrant church context. We must recognize the multiplicity of church models to embrace many different types of people. Simultaneously, church leaders must recognize the specific God-given calling for that church and not impose their own personal agenda upon it.

Generational Transition Process

We see five basic stages in the generational transition process. First, the planting stage is when a new immigrant church is planted to reach immigrants. Usually children’s ministry (CM) is in its infancy and youth ministry does not exist. Often these immigrant churches meet in the facilities of an Anglo church, and sometimes the educational ministry will be shared with that Anglo church.

Second, the stabilizing of the immigrant congregation occurs as the congregation establishes a solid membership, cultivates financial resources, and foundation is laid for their own educational ministry. Sometimes the children’s ministry (CM) remains in the mother tongue, while the youth ministry (YM) usually adapts English. Generally, the church struggles to find volunteers to serve in the educational ministry because of language barriers, reflecting the language barriers between the parents and children’s generations.

Third, the flourishing of the immigrant congregation as it often purchases its own building, develops its own niche. Children’s ministry usually adopts English as its primary language during this stage. The church begins to struggle to find a place for their English-speaking children as they grow into adulthood and often leave the church. This stage can be prolonged if immigration patterns remain strong in the area, as new immigrants feed into a flourishing immigrant church. Such growth can cloak the underlying challenges of reaching the next generation. However, when the challenges of reaching the next generation often push the church to the next stage.

Fourth, the empowering by the immigrant congregation releases leadership to the next generation, just as the Hebraic leaders gave leadership to the Hellenistic deacons in Acts 6. This empowering invites the next generation to the table of leadership, whether in a shared governance structure or in the development of an independent governance structure. Regardless of the structure, the next generation is given the privilege and responsibility to articulate and execute their mission through the church.

Finally, the birthing from the immigrant congregation of a next generation church occurs. This can happen in many different ways. Sometimes the next generation church becomes an independent church plant, while the first generation congregation continues to grow. This model is best when immigration patterns remain strong. At other times, the immigrant congregation shrinks as immigration decreases and the next generation congregation absorbs the immigrant congregation. This model is more important as immigration decreases to shrink the pool of new immigrants.

Models of Next Generation Ministry

As the generational transition process makes clear in stage 5, there are two directions that the immigrant church can take in birthing a next generation congregation. It can release the next generation as a separate, independent congregation, and it can be absorbed into the next generation as a sub-ministry or congregation. Different models will reach different types of people.

Beginning with stage three, we assume a fully mature second generation church member. They are usually highly educated and working. What models of ministry/church reach them?

English ministries of immigrant churches (stage 3).

Financially and politically independent English congregation existing side by side with an immigrant congregation (stage 4; e.g. Chinese Christian Union Church, Chicago)

Campus ministries (Eg. CRU and InterVarsity Christian Fellowship)

Financially and politically independent English congregation geographically removed from the immigrant congregation (stage 5; Harvest Community Church, Hoffman Estates).

Financially and politically independent English congregation caring for an immigrant ministry (stage 5; Lakeview Covenant Church, Chicago).

Multiethnic church plant with second generation leadership. (e.g., Covenant Fellowship Church, Urbana; New Life Community Church, Chicago; New Song Church, Irvine, CA)

Assimilation into a predominantly Anglo church (e.g. Harvest Bible Chapel, Rolling Meadows; Redeemer Presbyterian Church, New York).

1 Paul Taylor et. al., “Second Generation Americans: A Portrait of the Adult Children of Immigrants,” Pew Research Center Social and Demographic Trends (February 7, 2013); accessed at: http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/files/2013/02/FINAL_immigrant_generations_report_2- 7-13.pdf.

2 See further discussion on this in Mitchell Kim, David Lee, “Intergenerational Ministry: Why Bother?” Honoring the Generations: Learning with the Asian North American Church (M. Sydney Park, Soong Chan Rah, Al Tizon, eds.; Valley Forge, PA: Judson, 2012), 21–38.

Further Recommended Resources

Alumkal, Antony William. 2003. Asian American Evangelical Churches Race, Ethnicity, and Assimilation in the Second Generation. New York: LFB Scholarly Pub. LLC.

Biney, Moses. 2011. From Africa to America : Religion and Adaptation Among Ghanaian Immigrants in New York. New York: New York University Press.

Cha, Peter, Steve Kang, and Helen Lee. 2006. Growing Healthy Asian American Churches. Downers Grove, IL: IVP Books.

Chen, Carolyn. 2008. Getting Saved in America: Taiwanese Immigration and Religious Experience. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Dean, Kenda. 2010. Almost Christian: What the Faith of Our Teenagers Is Telling the American Church. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press.

--------. 2004. Practicing Passion: Youth and the Quest for a Passionate Church. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans Pub.

Ecklund, Elaine. 2006. Korean American Evangelicals: New Models for Civic Life. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press.

Foley, Michael, and Dean R. Hoge. 2007. Religion and the New Immigrants: How Faith Communities Form Our Newest Citizens. Oxford ;;New York: Oxford University Press.

Fong, Timothy P. 2002. The Contemporary Asian American Experience: Beyond the Model Minority. 2nd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Fowler, James W. 1981. Stages of Faith: The Psychology of Human Development and the Quest for Meaning. San Francisco: Harper & Row.

George, Sam, and T. V. Thomas, ed. 2012. Malayali Diaspora: From Kerala to the Ends of the World. New Delhi: Serials Publications.

Heft, James. 2006. Passing on the Faith : Transforming Traditions for the Next Generation of Jews, Christians, and Muslims. New York: Fordham University Press.

Hertig, Young Lee. 2001. Cultural Tug of War: The Korean Immigrant Family and Church in Transition. Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press.

Holli, Melvin G, Jones Peter, and Peter d’ Alroy Jones, ed. 1994. Ethnic Chicago: A Multicultural Portrait. Grand Rapids, MI.: W.B. Eerdmans Pub. Co.

Jeung, Russell. 2005. Faithful Generations: Race and New Asian American Churches. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Kim, Rebecca Y. 2006. God’s New Whiz Kids? Korean American Evangelicals on Campus. New York: New York University Press.

Kim, Sharon. 2010. A Faith of Our Own: Second-Generation Spirituality in Korean American Churches. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Kitano, Harry H. L, and Roger Daniels. 1988. Asian Americans: Emerging Minorities. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 10

Prentice Hall.Kwon, Ho, Kwang Chung Kim, and Stephen Warner. 2001. Korean Americans and Their Religions: Pilgrims and

Missionaries from a Different Shore. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press.Lee, Sang, and John V Moore. 1993. Korean American Ministry: A Resource Book. Expanded English ed.

Louisville: General Assembly Council Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.).

Matsuoka, Fumitaka. 2003. Realizing the America of Our Hearts: Theological Voices of Asian Americans. 1st ed. St. Louis, MO: Chalice Press.

Min, Pyong. 2010. Preserving Ethnicity Through Religion in America: Korean Protestants and Indian Hindus Across Generations. New York: New York University Press.

Min, Pyong Gap. 2002. The Second Generation: Ethnic Identity Among Asian Americans. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press.

———. 2005. Asian Americans: Contemporary Trends and Issues. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Min, Pyong, and Jung Ha Kim. 2002. Religions in Asian America: Building Faith Communities. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press.

Numrich, Paul. 2009. The Faith Next Door: American Christians and Their New Religious Neighbors. Oxford ;;New York: Oxford University Press.

Park, M. Sydney, Soong-Chan Rah, and Al Tizon. 2012. Honoring the Generations: Learning with Asian North American Congregations. Judson Press.

Rangaswamy, Padma. 2000. Namast America: Indian Immigrants in an American Metropolis. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Smith, Christian, Kari Marie Christoffersen, Hilary Davidson, and Patricia Snell Herzog. 2011. Lost in Transition: The Dark Side of Emerging Adulthood. New York: Oxford University Press.

Smith, Christian, and Patricia Snell. 2009. Souls in Transition: The Religious and Spiritual Lives of Emerging Adults. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press.

Takaki, Ronald. 1989. Strangers from a Different Shore: A History of Asian Americans. 1st ed. Boston, MA: Little Brown..

Tseng, Timothy, and Viji Nakka-Cammauf. 2009. Asian American Christianity Reader. Castro Valley, CA: Pacific Asian American & Canadian Christian Education Project and the Institute for the Study of Asian American Christianity.

Yang, Fenggang. 1999. Chinese Christians in America: Conversion, Assimilation, and Adhesive Identities. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Yep, Jeanette and Peter Cha eds. 1998. Following Jesus Without Dishonoring Your Parents. Downers Grove, IL: IVP.

Under point 2 I believe it should be Gen 9:18-26